Scene flow has been a fundamental element in filmmaking since the earliest days of cinema, evolving dramatically from rudimentary transitions to sophisticated visual storytelling techniques. The way directors manage the three-dimensional movement and flow between scenes has transformed how stories are told on screen, creating more immersive and emotionally resonant experiences for viewers. This evolution of scene flow represents one of the most significant developments in cinematic language, influencing everything from blockbuster films to independent productions.

Understanding scene flow in filmmaking means recognizing how the movement and progression between scenes creates a cohesive narrative structure. Unlike its technical counterpart in computer vision (which refers to three-dimensional motion fields), cinematic scene flow encompasses the artistic transitions, pacing, and visual continuity that guide viewers through a story. The masterful use of scene flow techniques has become a hallmark of exceptional filmmaking, allowing directors to manipulate time, space, and emotion with increasing sophistication.

As we examine the evolution of scene flow from classic cinema to contemporary productions, we’ll discover how technological advancements, changing audience expectations, and innovative directorial approaches have transformed this essential aspect of visual storytelling. The journey from then to now reveals not just technical progress, but a deeper understanding of how visual narrative flows can engage viewers on multiple levels.

The Birth of Scene Flow: Early Cinema Transitions

Photo by Yaroslav Shuraev on Pexels

In the nascent days of filmmaking, scene flow was primitive by necessity. Early silent films of the late 19th and early 20th centuries relied almost exclusively on hard cuts between static camera positions. Directors like Georges Méliès and the Lumière brothers were pioneers who worked within severe technical limitations, yet still managed to create narrative coherence through careful scene arrangement. The famous “A Trip to the Moon” (1902) by Méliès demonstrated early attempts at creating flow between scenes through theatrical staging and camera positioning.

The introduction of basic transitions marked the first significant evolution in scene flow. Fade-ins, fade-outs, and dissolves became the primary tools for early filmmakers to indicate the passage of time or change of location. These techniques, while simple by today’s standards, represented revolutionary advancements in visual storytelling. D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation” (1915), despite its deeply problematic content, showcased innovative cross-cutting techniques that enhanced narrative flow between parallel storylines.

As silent cinema matured, directors began developing more sophisticated approaches to scene flow. F.W. Murnau’s “The Last Laugh” (1924) featured the “unchained camera” technique, where fluid camera movements created seamless transitions between scenes. Similarly, Abel Gance’s “Napoleon” (1927) experimented with multiple screens and innovative editing patterns that expanded the possibilities of visual storytelling. These early innovations laid the groundwork for scene flow as a deliberate artistic choice rather than merely a functional necessity.

The transition to sound cinema in the late 1920s initially regressed scene flow techniques, as bulky sound recording equipment limited camera movement. However, this technical challenge forced filmmakers to focus on dialogue and performance timing as elements of scene flow. Directors like Ernst Lubitsch developed the “Lubitsch touch,” using witty dialogue and precise timing to create smooth narrative progression between scenes. This period demonstrated that scene flow wasn’t solely dependent on visual techniques but could be enhanced through careful attention to pacing and performance.

The Golden Age: Classical Hollywood Scene Flow

Photo by Max Vakhtbovycn on Pexels

The establishment of the Hollywood studio system in the 1930s and 1940s brought standardization to scene flow techniques. Classical Hollywood cinema developed a “invisible editing” approach that prioritized narrative clarity and emotional continuity over drawing attention to technical aspects. This period saw the refinement of the 180-degree rule, match cuts, and establishing shots—all designed to create seamless transitions between scenes while maintaining audience orientation within the story world.

Directors like Alfred Hitchcock elevated scene flow to an art form during this era. In films like “Rope” (1948), Hitchcock experimented with long takes and hidden cuts to create the illusion of a single, unbroken scene flow throughout the entire film. His masterful manipulation of suspense relied heavily on controlling the rhythm and pacing between scenes. Similarly, Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane” (1941) revolutionized scene flow through innovative transitions that compressed time and space, such as the famous breakfast table sequence that depicts the deterioration of a marriage through a series of brief scenes flowing seamlessly together.

The musical genre particularly showcased the importance of scene flow during this period. Films like “Singin’ in the Rain” (1952) demonstrated how choreographed movement could create natural transitions between narrative scenes and musical numbers. The dance sequences weren’t merely entertaining interludes but served to advance character development and plot while maintaining visual momentum. This integration of performance and narrative represented a sophisticated understanding of how scene flow affects audience engagement.

Film noir of the 1940s and 1950s introduced distinctive approaches to scene flow that emphasized psychological tension. Directors like Billy Wilder and Fritz Lang used shadow play, unusual camera angles, and disorienting transitions to create a sense of unease and moral ambiguity. The scene flow in films like “Double Indemnity” (1944) and “The Big Heat” (1953) reflected the protagonists’ increasingly complicated circumstances through increasingly fragmented visual transitions, demonstrating how scene flow could externalize internal character states.

New Waves and Experimental Approaches to Scene Flow

Photo by cottonbro studio on Pexels

The post-war period saw international film movements deliberately challenging Hollywood’s established scene flow conventions. The French New Wave filmmakers of the late 1950s and 1960s, including Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, intentionally disrupted traditional scene flow with jump cuts, handheld camera work, and discontinuous editing. Godard’s “Breathless” (1960) famously employed jarring jump cuts that called attention to the film’s construction while creating a sense of urgency and spontaneity that matched its protagonist’s lifestyle.

Italian Neorealism and later the cinema of Michelangelo Antonioni explored scene flow through long takes and deliberate pacing. Films like “L’Avventura” (1960) used extended sequences with minimal cutting to create a sense of existential drift, where the scene flow (or intentional lack thereof) reflected the characters’ emotional disconnection. This approach demonstrated how scene flow could be manipulated not just for narrative efficiency but to create specific psychological effects on the audience.

In Japan, directors like Akira Kurosawa and Yasujirō Ozu developed distinctive approaches to scene flow that influenced global cinema. Kurosawa’s dynamic action sequences in films like “Seven Samurai” (1954) used multiple camera setups and precise editing to create fluid, energetic scene transitions. In contrast, Ozu’s static camera positions and “pillow shots” (transitional scenes of landscapes or empty rooms) in films like “Tokyo Story” (1953) created a meditative scene flow that encouraged contemplation between narrative developments.

The 1970s saw American filmmakers incorporating these international influences while developing their own innovative approaches to scene flow. Directors like Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola created distinctive visual styles where scene transitions became signature elements. The famous Copacabana tracking shot in Scorsese’s “Goodfellas” (1990) demonstrated how a single, unbroken movement could efficiently establish character, setting, and social dynamics. Similarly, the intercutting between the baptism and assassinations in Coppola’s “The Godfather” (1972) created a powerful juxtaposition through carefully orchestrated scene flow.

The Digital Revolution: Scene Flow Transformed

Photo by Google DeepMind on Pexels

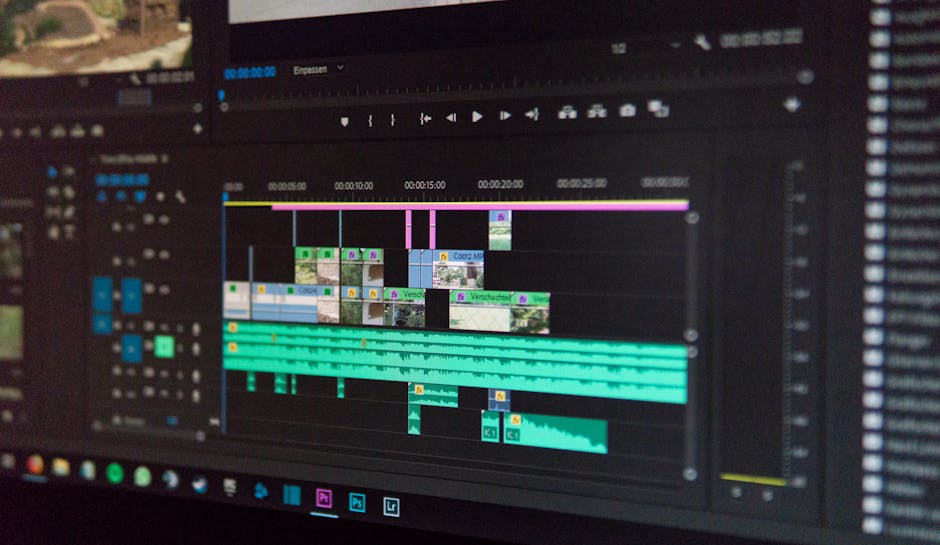

The advent of digital filmmaking technologies in the 1990s and 2000s dramatically expanded the possibilities for scene flow manipulation. Computer-generated imagery (CGI) and digital editing systems allowed filmmakers to create transitions that would have been impossible in the analog era. Films like “The Matrix” (1999) introduced revolutionary “bullet time” effects that allowed the camera to appear to move around frozen action, creating a distinctive flow between moments within a single scene that influenced countless subsequent productions.

Directors like David Fincher embraced digital technologies to create meticulously controlled scene flow. In films like “Fight Club” (1999) and “The Social Network” (2010), Fincher used digital tools to create precise camera movements, seamless transitions, and subtle visual effects that enhanced narrative progression while maintaining a distinctive visual style. The opening credit sequence of “Panic Room” (2002), with text integrated into the physical environment of the city, demonstrated how digital techniques could create flowing transitions between text and image.

The rise of non-linear storytelling in mainstream cinema also transformed approaches to scene flow. Christopher Nolan’s films, particularly “Memento” (2000) and “Inception” (2010), challenged audiences with complex temporal structures that required innovative scene flow techniques to maintain coherence. Nolan’s approach often involved visual or auditory motifs that created connections between non-chronological scenes, helping viewers navigate complicated narrative structures while maintaining emotional engagement.

Television production also experienced a revolution in scene flow techniques during this period. Shows like “Breaking Bad” and “Mad Men” brought cinematic approaches to the small screen, with sophisticated visual transitions and temporal manipulations previously rare in television. The rise of streaming platforms further blurred the boundaries between film and television, encouraging experimentation with episode length and structure that affected how scenes flowed within and between episodes. This evolution demonstrated how scene flow techniques had become central to visual storytelling across media formats.

Contemporary Scene Flow: Immersion and Interactivity

Photo by Mikhail Nilov on Pexels

Today’s filmmakers have access to an unprecedented array of tools for manipulating scene flow, resulting in increasingly immersive viewing experiences. Directors like Alfonso Cuarón and Sam Mendes have created films built around the illusion of continuous action. Cuarón’s “Children of Men” (2006) features several extended single-take action sequences that maintain unbroken scene flow through technically complex environments. Similarly, Mendes’ “1917” (2019) was designed to appear as a single continuous shot following soldiers through World War I trenches, creating an immediate, urgent scene flow that pulls viewers into the characters’ experience.

Virtual reality (VR) and interactive storytelling have introduced entirely new dimensions to scene flow considerations. Unlike traditional cinema, where directors control exactly what viewers see and when, VR experiences must account for audience agency in determining viewing direction and sometimes even narrative progression. This has led to innovative approaches where scene flow must work regardless of where the viewer chooses to look, creating new challenges and opportunities for visual storytellers working in immersive media.

The influence of video games on cinematic scene flow has become increasingly apparent in action-oriented films. Directors like Chad Stahelski (“John Wick” series) have created distinctive visual styles that incorporate game-like progression through environments, with fluid camera movements following characters through complex action sequences. This approach creates a scene flow that feels participatory and kinetic, reflecting the interactive experiences many viewers are familiar with from gaming.

Social media and short-form video platforms have also influenced contemporary approaches to scene flow. The need to capture attention quickly in platforms like TikTok and Instagram has led to accelerated editing patterns and distinctive transition styles that have subsequently influenced mainstream filmmaking. This cross-pollination demonstrates how scene flow continues to evolve in response to changing media consumption habits and technological possibilities.

The Future of Scene Flow: AI and Beyond

Photo by Steve Johnson on Pexels

As we look toward the future, emerging technologies promise to further transform scene flow techniques in filmmaking. Artificial intelligence is already being used to assist with editing decisions, suggesting optimal cut points and transitions based on analysis of successful films. While currently supplementary to human creativity, these tools may eventually develop sophisticated enough understanding of scene flow principles to generate complete editing patterns or suggest innovative transitions that human editors might not consider.

Real-time rendering technologies, already used in productions like “The Mandalorian,” are changing how scenes flow during the production process itself. By replacing traditional green screens with LED walls displaying computer-generated environments that respond to camera movement, these systems allow directors and actors to see the final scene composition during filming. This immediate visual feedback enables more precise control over how elements within and between scenes will flow in the final product.

The growing sophistication of deepfake technology and digital humans raises intriguing possibilities for scene flow manipulation. Future productions might seamlessly blend archival footage with newly created content, or age and de-age actors within a single continuous shot. These capabilities could fundamentally change how filmmakers approach temporal scene flow, potentially allowing single scenes to span decades of a character’s life without traditional cuts or transitions.

As audience viewing habits continue to evolve, so too will approaches to scene flow. The binge-watching model popularized by streaming services has already influenced how television episodes begin and end, with less need for recaps and cliffhangers when viewers immediately continue to the next episode. Similarly, interactive storytelling formats like Netflix’s “Bandersnatch” experiment with viewer-directed narrative branches that require rethinking traditional scene flow to accommodate multiple potential paths through the story.

Conclusion: The Enduring Importance of Scene Flow

The evolution of scene flow in filmmaking reflects broader changes in technology, artistic sensibilities, and audience expectations. From the simple cuts of early silent films to today’s complex digital manipulations, the way scenes transition and flow into one another has become an increasingly sophisticated aspect of visual storytelling. What remains constant throughout this evolution is the fundamental purpose of scene flow: to guide viewers through narrative experiences with clarity, emotion, and impact.

Great filmmakers have always understood that scene flow is more than a technical consideration—it’s a powerful tool for shaping how audiences experience stories. Whether through the classical continuity of Golden Age Hollywood, the disruptive innovations of international film movements, or the immersive techniques of contemporary digital cinema, scene flow techniques reflect directorial intent and creative vision. The most effective approaches to scene flow often become invisible to casual viewers precisely because they work so well at maintaining engagement with the story rather than its technical construction.

As we’ve seen throughout this exploration, scene flow continues to evolve in response to new technologies and changing media landscapes. The principles that guide effective scene transitions, however, remain rooted in fundamental storytelling considerations: maintaining clarity, controlling pacing, creating emotional resonance, and guiding viewer attention. These enduring principles ensure that even as specific techniques change, the art of scene flow will remain central to effective visual storytelling.

For both creators and audiences, understanding the evolution of scene flow provides valuable context for appreciating the craft of filmmaking. Recognizing how directors manipulate transitions, pacing, and visual continuity enriches the viewing experience and deepens appreciation for the artistry involved. As cinema continues to evolve, scene flow will undoubtedly remain a crucial element in the filmmaker’s toolkit—one that continues to be refined and reimagined with each new generation of visual storytellers.

Sources

- https://www.ri.cmu.edu/project/scene-flow/

- https://cvg.cit.tum.de/research/sceneflow

- https://library.fiveable.me/screenwriting-i/unit-7/transitions-scene-flow/study-guide/X7pHV2t2fPOgzzcU

- https://lmb.informatik.uni-freiburg.de/resources/datasets/SceneFlowDatasets.en.html

- https://www.ri.cmu.edu/pub_files/pub2/vedula_sundar_1999_1/vedula_sundar_1999_1.pdf