The concept of scene flow has been fundamental to cinematic storytelling since the earliest days of film, though its application and techniques have undergone remarkable transformation. Scene flow, at its core, represents the movement and transition between scenes that creates a cohesive narrative experience for viewers. Just as in technical terms scene flow refers to the three-dimensional motion field of points in space, in cinematic language it describes how directors guide audiences through the story space, connecting emotional beats and plot points into a seamless whole.

From the rigid formulas of classic Hollywood to the experimental approaches of modern filmmakers, scene flow has evolved dramatically alongside technological advancements and changing audience expectations. This evolution reflects not just technical progress but deeper shifts in how stories are told and experienced. The careful orchestration of scene flow remains one of the most powerful yet subtle tools filmmakers use to engage viewers on both conscious and subconscious levels.

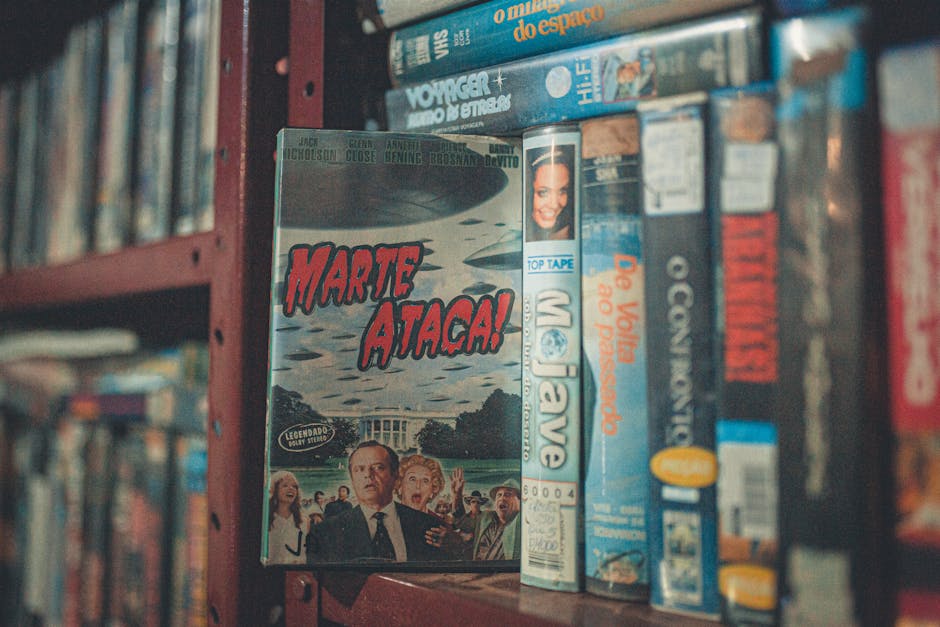

The Golden Age: Classic Hollywood Scene Flow Techniques

Photo by cottonbro studio on Pexels

During cinema’s Golden Age (roughly the 1920s through the 1950s), Hollywood developed a standardized approach to scene flow that prioritized clarity and continuity above all else. This era established many of the foundational techniques that would influence filmmaking for decades to come. Directors like Alfred Hitchcock, John Ford, and Howard Hawks mastered the art of guiding viewers through narratives with invisible precision.

The classic Hollywood style relied heavily on the 180-degree rule, match cuts, and establishing shots to maintain spatial coherence. Scenes typically followed a predictable pattern: establish the location, introduce the characters, develop the action, and then transition smoothly to the next scene. These transitions were often accomplished through dissolves, fades, or wipes – visual cues that signaled the passage of time or change in location.

Consider how Casablanca (1942) uses scene flow to build its narrative. The film employs clear establishing shots of Rick’s Café before cutting to interior scenes, maintaining consistent spatial relationships between characters. Transitions between major sequences often use dissolves to indicate the passage of time, while maintaining thematic continuity. This methodical approach to scene flow created a sense of reliability for audiences – they always knew where they were in the story space.

The studio system further standardized scene flow through the use of continuity editing, which emphasized invisible cuts and seamless transitions. This approach minimized audience awareness of the filmmaking process itself, instead immersing viewers fully in the narrative. Scenes flowed into one another with deliberate pacing, rarely drawing attention to the transitions themselves.

What makes this era’s approach to scene flow particularly interesting is how it balanced technical constraints with artistic expression. Without modern digital tools, filmmakers had to plan scene transitions meticulously during production, often using practical effects and camera techniques to create smooth flow between sequences. This limitation often resulted in creative solutions that emphasized craftsmanship and planning.

New Wave Disruptions: Breaking the Rules of Scene Flow

Photo by Mikhail Nilov on Pexels

The emergence of various film movements in the 1950s and 1960s – particularly the French New Wave, Italian Neorealism, and later the New Hollywood era – deliberately challenged established scene flow conventions. Filmmakers like Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Federico Fellini rejected the invisible editing style of classic Hollywood, instead drawing attention to the constructed nature of film through jump cuts, discontinuity, and fragmented narratives.

Godard’s Breathless (1960) famously employed jump cuts that violated traditional scene flow expectations, creating a jarring yet energetic rhythm that reflected the protagonist’s chaotic lifestyle. Rather than smoothly transitioning between locations and time periods, these new wave directors embraced disorientation as an aesthetic choice. Scene flow became less about guiding viewers comfortably through a narrative and more about provoking emotional and intellectual responses through disruption.

In America, directors like Arthur Penn and Sam Peckinpah incorporated these influences while developing their own approaches to scene flow. Bonnie and Clyde (1967) used rapid editing and disorienting scene transitions during its violent sequences, creating a new vocabulary for how action could flow across scenes. The Wild Bunch (1969) pushed this further with its revolutionary use of multiple camera setups and editing that stretched and compressed time within and between scenes.

This era also saw the rise of non-linear storytelling, with films like Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961) deliberately confusing temporal relationships between scenes. The flow between sequences became a puzzle for viewers to decipher rather than a clear path to follow. These experimental approaches to scene flow reflected broader cultural shifts toward questioning established norms and embracing subjective experience.

What makes this period so significant in the evolution of scene flow is how it expanded the vocabulary of cinema. By breaking established rules, these filmmakers demonstrated that scene transitions could be expressive elements in themselves rather than merely functional connections. The disruption of traditional scene flow opened new possibilities for how stories could be structured and experienced.

The Blockbuster Era: Accelerated Scene Flow

Photo by Lucas Pezeta on Pexels

The late 1970s through the 1990s saw the rise of the modern blockbuster, bringing with it significant changes to how scene flow functioned in mainstream cinema. Directors like Steven Spielberg and George Lucas developed a more kinetic approach to scene transitions, influenced by television pacing and aimed at maintaining audience engagement through faster cutting and more dynamic movement between scenes.

Films like Star Wars (1977) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) employed scene flow techniques that emphasized momentum and energy. Scenes no longer lingered as they might have in earlier eras; instead, they propelled viewers forward through the narrative at an accelerated pace. This approach to scene flow often utilized action to transition between locations and plot points, creating a sense of constant movement.

The influence of music videos in the 1980s further transformed scene flow in mainstream cinema. Directors like Tony Scott and Adrian Lyne incorporated stylized transitions, dynamic camera movements, and rhythmic editing that created a more sensory experience. Top Gun (1986) exemplifies this approach, with its scene flow often dictated by musical cues and visual motifs rather than traditional narrative progression.

This era also saw innovations in how scene flow could compress time and space. The montage sequence, while not new to cinema, became increasingly sophisticated as a tool for conveying character development and plot progression efficiently. Films like Rocky (1976) used training montages to show character growth across time, while The Breakfast Club (1985) employed montages to show the developing relationships between characters within a compressed timeframe.

What distinguishes the blockbuster era’s approach to scene flow is its emphasis on audience engagement through pacing and spectacle. Scene transitions became less about maintaining spatial and temporal continuity (though these remained important) and more about sustaining emotional investment and excitement. This shift reflected changing audience expectations in an increasingly media-saturated environment where attention had to be continuously recaptured.

Digital Revolution: Scene Flow Unbound

Photo by cottonbro studio on Pexels

The digital revolution of the late 1990s and early 2000s fundamentally transformed how filmmakers approached scene flow. New technologies removed many of the physical constraints that had previously limited how scenes could transition and connect. Computer-generated imagery, digital editing systems, and eventually fully digital production pipelines created unprecedented freedom in manipulating time and space between scenes.

Films like The Matrix (1999) showcased how digital effects could create entirely new types of scene flow, with its “bullet time” sequences altering the perception of time within scenes and its virtual environments allowing for instantaneous transitions between different realities. Similarly, Fight Club (1999) used digital compositing to create seamless transitions that would have been impossible with traditional techniques, such as pulling through a trash can and emerging in an underground parking lot.

Directors like David Fincher and Christopher Nolan developed highly controlled approaches to scene flow that leveraged digital tools while maintaining meticulous attention to narrative structure. Fincher’s Zodiac (2007) uses digital compositing to create time-lapse sequences that compress years into moments, while Nolan’s Inception (2010) constructs complex nested dream sequences with parallel scene flow occurring at different temporal rates.

The digital era also saw the rise of what might be called “database narratives” – films like Run Lola Run (1998), Memento (2000), and Cloud Atlas (2012) that experiment with multiple timelines, alternate realities, and non-linear structures. These films require viewers to actively track and construct scene flow relationships rather than passively following a single narrative thread. The transitions between scenes in these films often function as puzzles or clues rather than simple connective tissue.

What makes this period revolutionary for scene flow is the removal of technical limitations that had previously constrained filmmakers’ imaginations. Digital tools allowed for scene transitions that could be simultaneously seamless and impossible – defying physics while maintaining narrative coherence. This freedom enabled directors to more closely align visual scene flow with the psychological and emotional experience of their characters and themes.

Contemporary Cinema: Hybrid Approaches to Scene Flow

Photo by Hardeep Singh on Pexels

Today’s filmmakers have inherited the full spectrum of scene flow techniques developed throughout cinema history, creating a contemporary landscape characterized by hybrid approaches that combine classical methods with digital innovations. Modern directors often shift between different scene flow styles within a single film, using each transition technique as a deliberate artistic choice rather than following a single formula.

Films like Birdman (2014) use digital technology to create the illusion of a single continuous take, eliminating traditional scene transitions entirely while still moving through different locations and time periods. This approach creates a uniquely immersive scene flow that mirrors the protagonist’s subjective experience. Conversely, directors like Wes Anderson embrace highly stylized, almost theatrical scene transitions in films like The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), using symmetrical compositions, whip pans, and deliberate camera movements to create a distinctive visual rhythm between scenes.

The influence of streaming television has also affected cinematic scene flow, with many films adopting techniques developed for long-form storytelling. The episodic structure of streaming shows has encouraged filmmakers to experiment with scene flow that builds across longer narrative arcs, sometimes sacrificing immediate clarity for eventual payoff. This approach is evident in films like Parasite (2019), which carefully controls information release through its scene transitions, gradually revealing connections between seemingly disparate elements.

Virtual production technologies, as used in The Mandalorian and other recent productions, are creating new possibilities for scene flow by allowing directors to visualize transitions between environments in real-time during shooting. This technology bridges the gap between production and post-production decisions about scene flow, potentially leading to more integrated approaches in the future.

What defines contemporary scene flow is its self-awareness and flexibility. Today’s filmmakers understand scene flow as a powerful narrative tool with its own history and vocabulary. They can choose to embrace classical continuity, jarring discontinuity, or anything in between based on the specific emotional and thematic needs of their stories. This freedom has led to increasingly sophisticated uses of scene flow to convey complex ideas about time, memory, and perception.

The Future of Scene Flow: Virtual Realities and Interactive Narratives

Photo by Artem Podrez on Pexels

As we look toward the future of cinema and visual storytelling, emerging technologies suggest fascinating new directions for scene flow. Virtual reality, augmented reality, and interactive narratives are already beginning to transform how audiences move through story spaces, potentially revolutionizing our understanding of scene transitions and connections.

Virtual reality filmmaking presents unique challenges and opportunities for scene flow. Without the frame of a traditional screen, directors must find new ways to guide viewer attention from one story element to another. Early VR narratives have experimented with spatial audio cues, lighting, and character movement to direct audience focus, essentially creating a more environmental approach to scene flow where transitions happen around the viewer rather than through cuts.

Interactive narratives like Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018) introduce another dimension to scene flow by allowing viewers to make choices that affect narrative progression. This creates branching scene flows where transitions must function regardless of which path the viewer chooses. Future developments in this area may lead to increasingly sophisticated adaptive scene flow that responds to viewer engagement and preferences in real-time.

Artificial intelligence is also beginning to influence scene flow through tools that can analyze and even generate editing patterns. While currently used primarily as assistive technology, AI could eventually develop new approaches to scene transitions based on analyzing vast datasets of existing films or by identifying optimal patterns for maintaining viewer engagement across scenes.

The growing convergence of film and gaming technologies suggests a future where scene flow becomes increasingly fluid and responsive. Games like The Last of Us Part II already incorporate cinematic scene flow techniques while maintaining player agency, creating hybrid experiences that blur the line between passive viewing and active participation. As these technologies continue to evolve, we may see entirely new forms of scene flow emerge that transcend traditional cinematic boundaries.

What makes this moment in the evolution of scene flow particularly exciting is its open-ended potential. Rather than replacing earlier approaches, new technologies are expanding the vocabulary of possible transitions and connections between narrative moments. The fundamental challenge remains the same – guiding audiences through story spaces effectively – but the tools and techniques for meeting this challenge continue to multiply in fascinating ways.

Conclusion: The Enduring Importance of Scene Flow

Photo by Kyle Loftus on Pexels

Throughout the evolution of cinema, from the earliest silent films to today’s digital spectacles, scene flow has remained a fundamental element of effective storytelling. While the techniques and technologies have transformed dramatically, the essential purpose of scene flow has remained constant: to guide viewers through narrative space and time in ways that create meaningful experiences.

What makes scene flow so crucial to cinematic art is its dual nature – it functions both technically and emotionally. At the technical level, scene flow provides the connective tissue that holds a film together, establishing spatial and temporal relationships that allow viewers to follow the story. At the emotional level, it shapes how audiences experience the rhythm and momentum of a narrative, influencing their engagement and response to the material.

The most successful filmmakers throughout history have understood that scene flow is never merely functional. The way a director transitions from one scene to another can reinforce thematic elements, reveal character psychology, create suspense, or evoke specific emotional responses. From Hitchcock’s masterful suspense sequences to Wong Kar-wai’s dreamy temporal shifts, scene flow has been a powerful tool for artistic expression.

As we’ve traced the evolution of scene flow from classic Hollywood to contemporary digital filmmaking and beyond, what becomes clear is that each new approach doesn’t simply replace what came before. Rather, the vocabulary of possible scene transitions continues to expand, giving filmmakers an increasingly rich palette of techniques to draw from. Today’s directors can choose from this full spectrum of approaches based on their specific artistic goals.

In an age of fragmented media consumption and shortened attention spans, thoughtful scene flow may be more important than ever. The ability to guide viewers smoothly through complex narratives, maintain engagement across different story elements, and create meaningful connections between scenes remains essential to successful storytelling. As cinema continues to evolve alongside new technologies and changing audience expectations, scene flow will undoubtedly continue to transform – but its fundamental importance to the art of film will endure.

Sources

- https://www.ri.cmu.edu/project/scene-flow/

- https://cvg.cit.tum.de/research/sceneflow

- https://library.fiveable.me/screenwriting-i/unit-7/transitions-scene-flow/study-guide/X7pHV2t2fPOgzzcU

- https://paperswithcode.com/task/scene-flow-estimation/codeless

- https://www.ri.cmu.edu/pub_files/pub2/vedula_sundar_1999_1/vedula_sundar_1999_1.pdf